Find what's within your control

The Overlap #32

The Overlap is a newsletter somewhere between product development and organizational development. It comes out every other Wednesday.

I share a bit about my parents here. Partly because I’m reading Crying in H-Mart: a beautiful memoir about Michelle Zauner’s experience of her mom’s death. And partly because when I coach others on finding what’s within their control, I flashback to my parents telling this to my younger self.

Growing up, my parents told me never to complain and just work harder. Today, I complain a lot and don’t work that hard.

My dad is from Manila’s poorest neighborhood: Tondo. When you're in Tondo, you can breathe in the smell of trash on every street. Most children are malnourished. Of my friends and family who don’t live in Tondo, zero of them have been there.

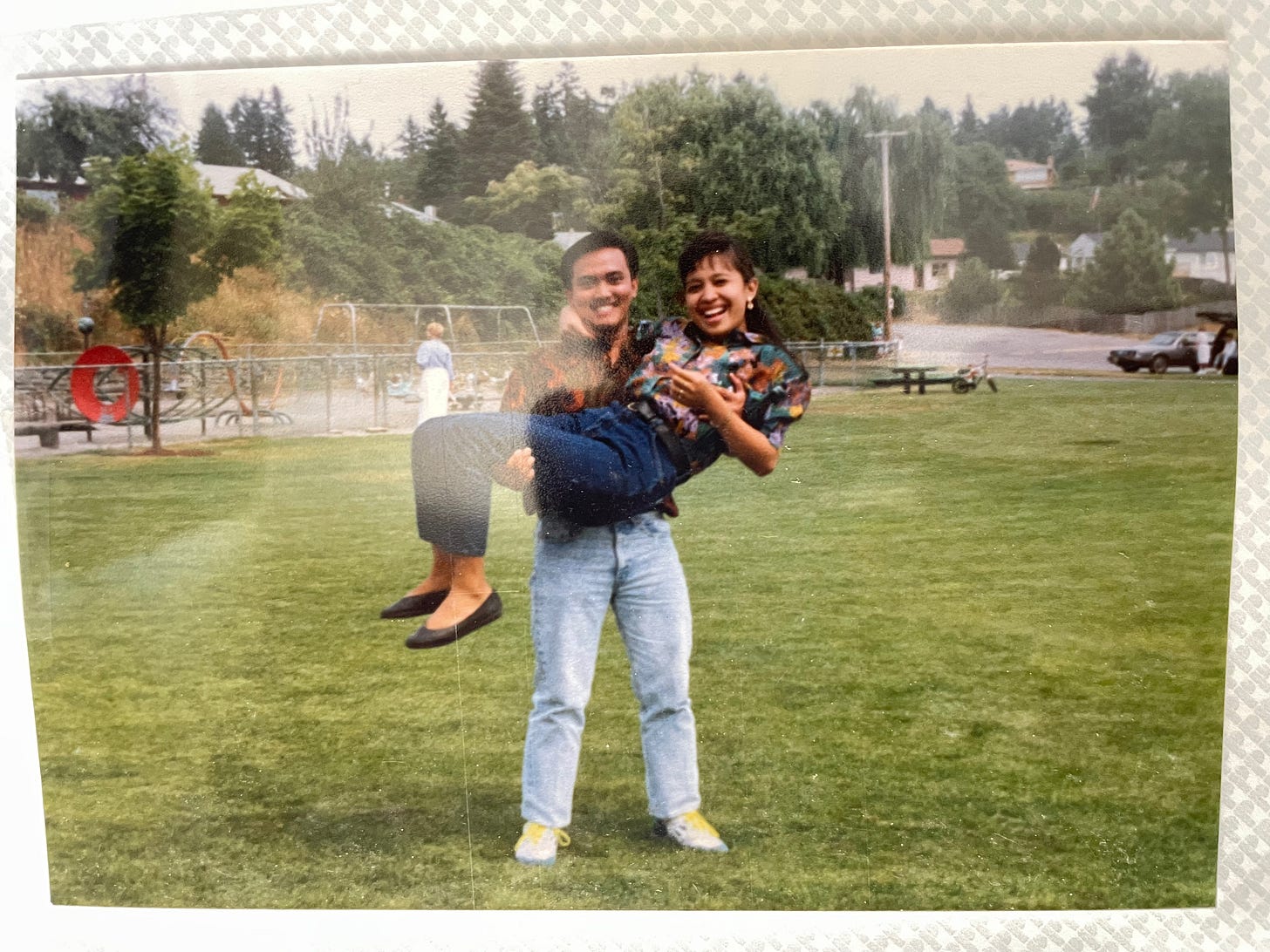

My dad studied electrical engineering at Mapua Institute of Technology, the “MIT” of the Philippines. Mapua offered him a teaching position, which he accepted. He met another teacher his age, Sen. They fell in love and married.

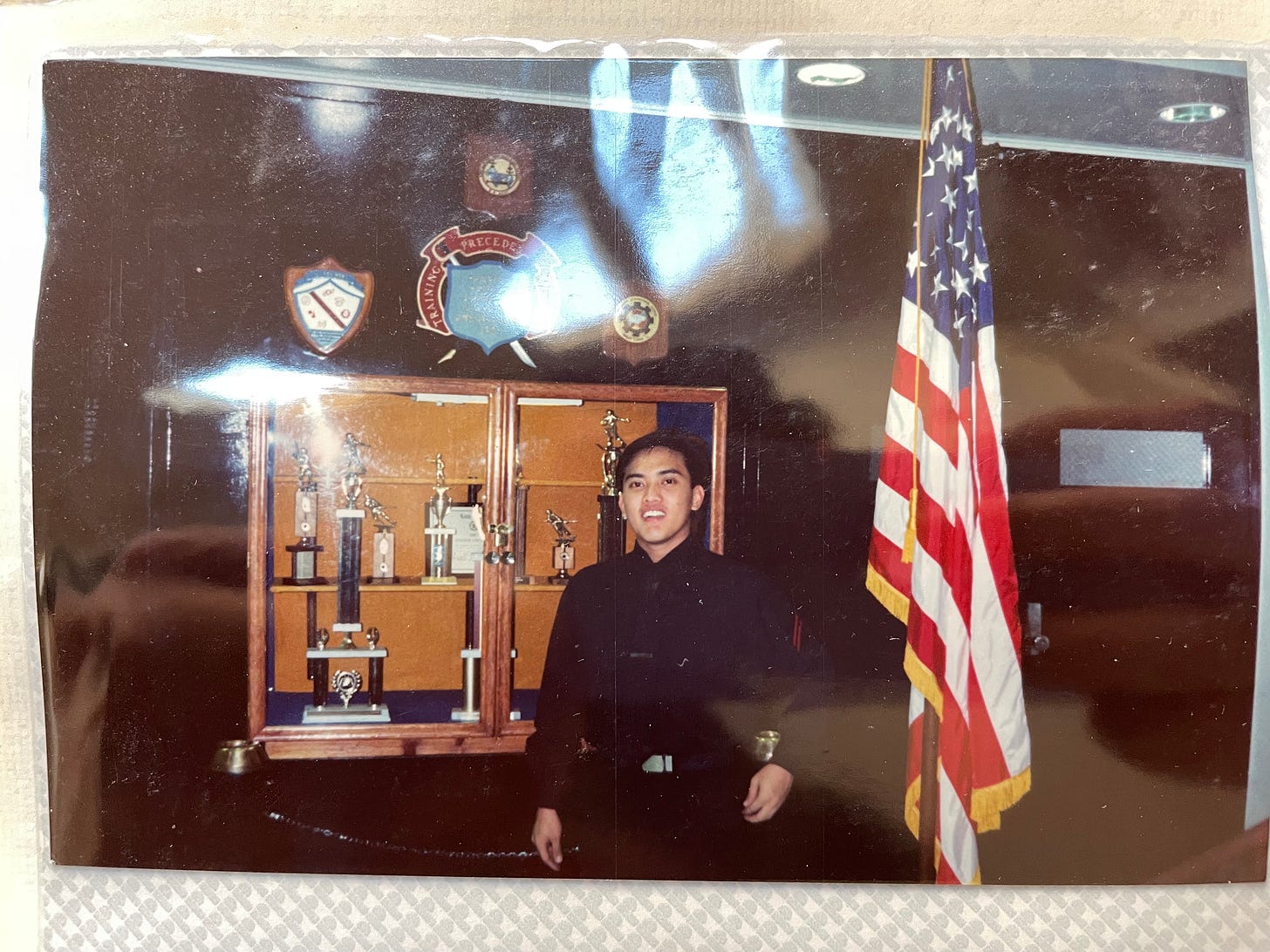

My dad tried his chance to make the US Navy. Only 400 Filipinos were allowed to enlist, per year. Your position? Wiping grease off the ship’s floor and cooking food for the “real” soldiers. As a Filipino, you aren’t trusted to steer a ship, hold a gun, or create a battle strategy. You’re meant to cook or clean.

My dad knew that this was a lottery. The prize? Being shat on by white supremacy. He did it anyway. He got into the US Navy. He studied the inner workings of how a ship, learned its backend, and fixed technical issues on the ships he worked in. He became Chief Petty Officer in 7 years—a feat that usually takes 12 years to achieve—and commanded a team. All after starting as a cleaner.

“How’d you do it, dad?”

“Don’t complain, just work harder.”

Don’t Complain, Just Work Harder

I could hear my parents saying that to me, to this day. The world grants more opportunities to white people than folks with my skin, so I have to work 200% harder than them. I have no other choice. Complaining is a waste of time.

I developed a work ethic. I practiced basketball every day after school. I was shorter than everyone else I played with, so I trained myself to be the fastest person on the court. I worked my ability to drive past bigger defenders because I couldn’t post them up. I showed up to practice before everyone else and stayed on the court when everyone else went home. I didn’t complain, I just worked harder.

I hated when my family went on vacation because I couldn’t practice basketball every day. Rest was in the way of practice. I can’t not practice.

Kobe was my hero growing up. He practiced at 5am every day and outworked everyone.

Those times when you get up early and you work hard, those times when you stay up late and you work hard, those times when you don’t feel like working, you’re too tired, you don’t want to push yourself, but you do it anyway. That is actually the dream. That’s the dream.

A High Locus of Control

I’ve been an INTJ on the Myers-Briggs personality test since I was in college. (Yes, I know the Myers-Briggs isn’t scientifically validated, but I’m a big believer in the value of reflection, even if the framework isn’t 100% scientific.)

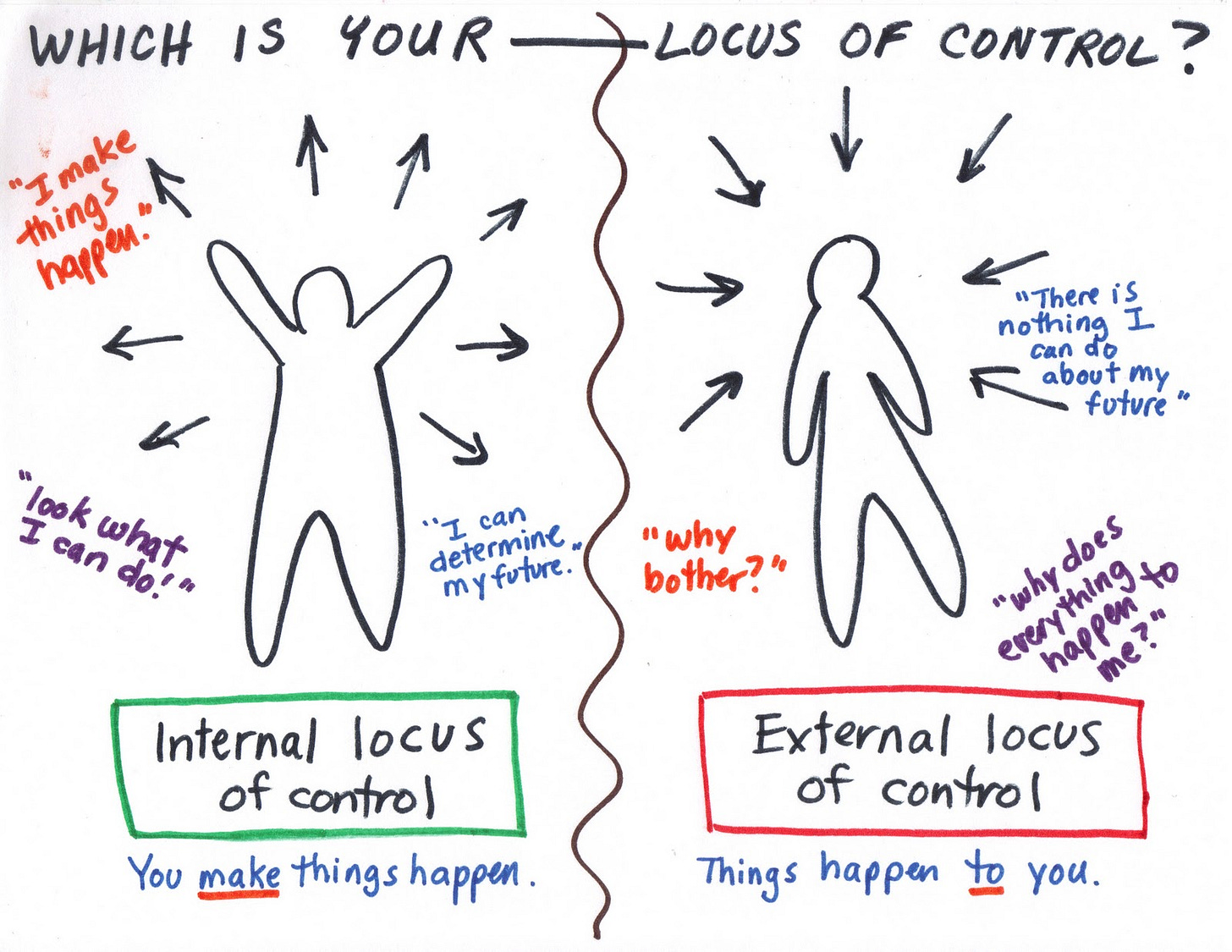

INTJs have a high internal locus of control. I make things happen; things don’t happen to me.

I’ve had a high locus of control because my dad did, too.

“Don’t complain. Just work harder. You do what you set your mind to.”

Systemic problems ≠ Complaints

My first job taught me all about systems thinking. At first, I thought naming problems of a system was a form of complaining. Complaining, in my then brain, was a waste of time — it gets in the way of working hard.

But more and more, I saw the power of framing problems. You can work hard on the wrong problem and not get the results you want. Framing the problem makes sure you solve the right problem; not framing problems puts your hard work to waste.

I used to think that complaining about software was a waste of time. I could hear my parents say “It’s free, isn’t it?! Who cares if it’s hard to use? Figure it out!”

But I’ve learned that these complaints can be the start of an elegant solution. Making the time to bitch about how hard it is to collaborate on Sketch has led to some of the most successful startups. Complaints, to an extent, are helpful!

Finding the balance between complaining and framing the problem

I catch myself complaining from time to time. I complain about being on video calls all the time (and not set boundaries for myself). I complain when I can’t find my MacBook charger. I complain about how much I have on my plate, which a) often isn’t that much and b) is assigned by — you guessed it — me.

Complaining is good if it frames the problem and leads to a solution. This isn’t to say that I’m against venting. Vent away! And create space for others to vent, too. You just have to draw the line when it’s counterproductive.

Find your locus of control

We have more agency over our problems than we might think.

When I used to consult for large financial institutions, the folks who complained the most were middle managers. It made sense. Middle managers…

have to pass down decisions they don’t agree with

don’t have much authority in their role to change systemic issues

have seen a bunch of failed change efforts

I found myself saying the same thing over and over to them: find what’s within your control to change. If you can’t change the way your higher-ups budget, you can change the way your p&l budgets. If you can’t change the overall organizational strategy, you have control over how your division achieves that strategy.

Learned helplessness is a behavior that we all do. We learn to be helpless after we fail to create change. Even when we’re persistent. So we feel jaded. We blame. We don’t take ownership of our circumstances.

Yes, it sucks that you can’t change the annual performance review process at your company. But can you set an example for how your performance review can be more peer-based with your team? Can you ask for feedback from your direct reports, to model a more peer-based way of evaluating performance?

We feel powerless. But we’re not!

Avoid learned helplessness. Assume you have some degree of agency to solve the problem. Even if the problem is systemic.

While it’s a good use of our energy to name what’s outside of our control, it isn’t a good use of our energy to assume that everything is outside of our control. It’s better to focus on what’s within our control, even in situations where mostly everything is outside of it.

This is what my dad did to move out of the poorest slum in Manila. He signed up for the Navy with slim odds. He became a Chief who ran ships and led teams when most Filipinos are cooks and chefs.

You have some degree of agency over the situation.

And yes, complain! Complaining will help you find what’s within your control. Once you find what’s within your control, get clear on what you want. Then make it happen. And if it doesn’t happen, learn why, what’s out of your control, and what you can do next time.

What I’m Reading

This edition of The Beautiful Mess. John shares thoughts on boards inspired by real teams. Nice to look at real-life examples now and then.

The dao of DAOs. Yes, it’s about time I go down the DAO (decentralized autonomous organization) rabbit hole. If you know of any DAOs that are focused on proving out alternative organizational structures themselves and/or helping others prove them out, let me know as a reply or in this Twitter thread.

What if, for example, you aimed to work 20% less than you had time to reasonably handle?

“[Understanding your needs] is the difference between feeling empty despite having ‘everything’ and feeling full despite having very little.”

See you in two weeks,

–tim