Company values aren’t actionable. Here’s how you can change that.

The Overlap #6

Update: I made this FigJam template! So if you’re a fan of even/over statements and FigJam, use this with your team.

Welcome to The Overlap, a biweekly newsletter that explores the relationship between product & organization design.

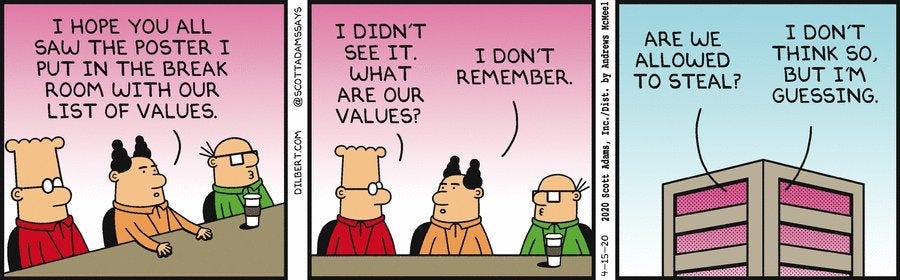

Every company loves to define their values. Yet, they’re rarely useful in my experience.

Don’t get me wrong: values are useful when done right. It’s just that they don’t inform my and my team’s decision-making. They aren’t actionable.

Think about it. When you’ve wrestled with a tough decision, have you ever revisited your company’s values of think different and integrity and thought “Great! I know what decision to make now.”? Me neither.

The way most companies employ values end up becoming anti-patterns: common responses to a recurring problem that backfire. Rodney Evans identifies three ways values can be counterproductive:

Leaders use values to force conformity. Some companies value “going above and beyond” and work 80 hour workweeks. But what if you value 40 hour workweeks? What if you personally get more work done in a 40 hour workweek than in an 80 hour workweek? You’re down to two choices: work 80 hours/week or 40 hours/week. You’re forced to sacrifice reputation or work-life balance, and that’s a shitty tradeoff.

Values often conflict with each other. For example, Twitter has two values that conflict with each other: “Innovate through experimentation” and “Be rigorous. Get it right.” When your team is 40% certain that a certain feature can lead to a major growth opportunity, will they experiment to get more data on whether it’s a big opportunity? Or will they get it right and decide not to pursue that feature?

Values ignore context. Values are created by leaders and pushed down to the rest of the organization. The very fact that they’re created in a silo with no input from the broader organization results in the values being ignored or paid lip service to. Sure, we’ll put “people over process” in our slide decks. But how does this even apply to my job?

So, how can we make values useful?

Turn them into even over statements.

What are even over statements?

Even over statements help us make hard decisions. When push comes to shove, we know what gives.

Even over statements are written like this:

A good thing even over another good thing

For example, take Twitter’s two conflicting values:

Innovate through experimentation. (Let’s shorten this to “experiment”)

Be rigorous. Get it right. (Let’s shorten this to “get it right”)

Let’s put the two into an even over statement:

Experiment even over get it right

Now, we have a statement that can guide our decisions. If you’re a product manager at Twitter and you’re 55% sure that a certain feature that will take 6 months to build could lead to $10M in revenue, you have the confidence to run an experiment and get data on whether this feature is worth pursuing.

If the even over statement were flipped to…

Get it right even over experiment

You’ll likely take the more conservative approach and decide not to pursue that feature, since you’re only 55% sure.

The point is that it forces you to be clear about what you’re willing to say no to. You’re empowered to make a bold tradeoff. Without these statements, you’ll continue to defer to leaders to make hard decisions for you—furthering your dependency on others and preventing the opportunity for you and your team to self-manage.

Examples of even over statements

Here are other examples:

Range even over affordability

Tesla chose to expand the range of the Model 3 even though this made it more expensive than initially intended.

Market share even over margin

Amazon won’t match Netflix’s margin with Prime Video. However, that’s intentional: Prime Video is a way to get folks to sign up for Amazon Prime.

Public health even over profit

In March of this year, almost every sports association suspended, postponed, or canceled their season to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Functionality even over feature parity

Microsoft doesn’t care about Teams lacking in design compared to Slack. They care about building a good enough product so that their Office 365 customers wouldn’t feel the need to purchase Slack.

To be clear, by writing an even over statement, you are not saying you don’t care about the value on the right. You’re just saying that the value on the left is more important at this moment. Amazon cares about margin, of course, but they care more about market share because they believe it’ll lead to better margin in the long-term.

A good way to test whether you wrote a useful even over statement is to reverse the statement and see if it leads to drastically different decisions. Let’s reverse the statements above:

Affordability even over range. Tesla wouldn’t expand the range of Model 3 to make it more affordable.

Margin even over market share. Amazon wouldn’t have started Prime Video.

Profit even over public health. Sporting events would not have shut down in March.

Feature parity even over functionality. Teams could be a much better product than it is today.

Reversing the statements lead to very different decisions. This is a sign that we wrote our statements well!

Here are two examples of bad even over statements:

Simplicity even over lack of focus. Remember, an even over statement is a good thing even over another good thing. “Lack of focus” is not a good thing. Consider feature parity or serving multiple segments.

Honest conversations even over avoidance. Again, “avoidance” isn’t a good thing. Consider keeping the peace or easeful conversations.

Good even over statements should make us a little uncomfortable because the tradeoff is real.

And a final note: treat even over statements as fluid, not static. Do not keep the same even over statement for over a year. Review them every quarter, and revise them based on what you learned in the previous quarter and what you need to accomplish in the next quarter.

Even over statements scale good decision making

I’ve written before that a leader’s job is to create tools for good decisions at every level:

“Leadership’s job isn’t oversight, it isn’t requirements building, it isn’t even really product direction. It’s to create tools for making good decisions at every level.”

Even over statements are that tool. They force teams to say no. They transform conflicting values into useful rules of thumb. And they will guide you when you’re at a fork in the road, resulting in you making a wise decision because you’re clear on what’s most important.

Shoutouts to The Ready for introducing me to even over statements in 2016.

What I’m Reading

Building an MVP is like serving a burnt pizza - Jiaona Zhang

We often lose sight of creating a product that users want when we’re focused on making sure it’s viable. Don’t forget to make sure your MVP is a thing users would love.

Independence, autonomy, and too many small teams - Kislay Verma

“The core idea behind autonomy is not arranging teams to maximize outputs of steps in the value chain, but defining value chains in such a way that a single, tight-knit team can be unleashed upon it.”

Less strategy, more structure - Clay Parker Jones

Large companies struggle with launching new growth opportunities because its big, matrixed structure gets in the way. Clay makes the case that large orgs should have less strategy (but bigger) and more structure (but smaller).

A big little idea called legibility - Venkatesh Rao

One of those essays that makes you question your world view. Most org change efforts happen because someone in authority believes their view is The One Best Way. We argue that our One Best Way is rational when really we fail to understand the dynamics and nuances of what we want to change. We seek legibility — “this system must confirm with my worldview” — instead of understanding. We must start with understanding the system before changing it.